If you see a wrong charge on your credit card, don’t worry. You can dispute the charge on your card — commonly called a chargeback or a credit card dispute — and you could get a full refund.

I’ll tell you how.

What is a credit card dispute?

A credit card dispute is when you ask your bank or credit card company to remove a charge from your bill.

In the United States, a 1975 law called the Fair Credit Billing Act (FCBA) gives you 60 days from the time you receive your credit card bill to dispute a charge.

There are similar, though lesser-known, protections for debit cards and money transfers. I’ll get to those in a moment.

In this guide, I’ll answer the following questions:

- What kinds of charges can I dispute?

- Are debit card purchases covered?

- How do I dispute a charge on my credit card?

I’ll also give you insider information that will help you prevail in your next credit card dispute.

What’s new in 2025?

There have been several changes in the law that affect your ability to dispute a charge.

- Stronger protections against subscription traps: Many credit card companies are now offering extended protections for recurring charges, particularly for subscriptions. If you didn’t explicitly sign up for a recurring service, you may have grounds for a chargeback.

- Global chargeback regulations: New regulations, especially in the EU under PSD2 (Payment Services Directive), require stronger consumer verification methods. That makes it harder for fraudsters to use stolen credit card information.

- Faster dispute resolution: In some regions, banks and credit card companies have been working to speed up the dispute process, particularly for smaller disputes under a specific threshold. This means quicker resolutions for consumers. Once your merchant has submitted evidence in a dispute, the issue is resolved within 24 hours.

What kinds of charges can I dispute?

The FCBA protects American consumers from unfair billing practices.

They include:

- Charges you didn’t authorize.

- Incorrect charges.

- Charges for goods or services not delivered.

- A good or service that was not as described by the merchant.

- Math errors or errors in calculating the total.

Note: The FCBA only covers “open-end” credit accounts like credit cards or charge accounts. It does not protect debit cards or money wired through a service like Zelle or PayPal. However, many electronic transactions are covered by a little-known rule called Regulation E.

What if I made my purchase with a debit card?

The Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA), also known as Regulation E, offers consumer protections for electronic fund transfers, including debit card transactions.

EFTA allows consumers to dispute errors related to their debit cards. The regulation defines an error as:

- An unauthorized electronic funds transfer.

- An incorrect transfer to or from the consumer’s account.

- The omission of an EFT from a periodic statement.

- An error made by the financial institution relating to the transfer.

- Receiving an incorrect amount of money from an ATM.

- A transfer not identified on an ATM receipt or periodic statement, or in connection with a preauthorized transfer to your account.

The EFTA resolution process is less structured than that of the FCBA. The law states that after a financial institution receives oral or written notice of an error from you, it must do the following:

- Promptly investigate the oral or written allegation of error.

- Complete its investigation within the time limits specified in the regulation.

- Report the results of its investigation to the customer within three business days after completing its investigation.

- Correct the error within one business day after determining that an error has occurred.

The protections under EFTA aren’t as broad as those afforded credit card holders. The law doesn’t include the right to dispute a transaction because of a problem with goods or services. It’s strictly limited to errors. Yet few debit card holders know about these consumer protections.

What are the requirements for a credit card dispute?

The law has some peculiarities that are worth noting:

The transaction must be $50 or more

The purchase must be $50 or more. It has to be made in your home state or within 100 miles of your home address. This rule doesn’t apply if the merchant is affiliated with the bank that issued the card, or if you relied on an advertisement supplied by the issuing bank.

It has to be in writing

You have to initiate a dispute in writing. Some banks will accept disputes by telephone. But disputing by telephone does not preserve your rights under the FCBA. Once you dispute a charge, the bank must acknowledge the dispute within 30 calendar days, and it must resolve the dispute within 90 days.

You must give the merchant a chance to work it out

Under the FCBA, you must make a “good faith” effort to resolve the problem with the merchant before disputing the charge.

Pro tip: If no online form is provided to initiate your dispute, mail the dispute via certified mail or other trackable methods to provide proof of delivery. Remember, you must initiate the dispute within 60 days of the first statement in which the error or charge appeared. Some banks extend this deadline, but they don’t have to.

What if it takes longer than 60 days to dispute my charge?

It often takes longer than 60 days to initiate a credit card dispute. For example, say you book a cruise vacation for next year. The clock would start ticking when you completed the purchase, leaving you with no consumer protection during your vacation.

Or would it?

Fortunately, credit card agreements often extend the time you can have to file a dispute. But neither merchants nor credit card issuers are always aware of these provisions.

For example, American Express cardholders have up to 120 days from the transaction date to dispute the charge, except for goods and services not received or returned goods.

MasterCard’s service agreement has a provision for failed travel service providers, such as airlines and cruise lines. Under certain circumstances, you have a maximum of 150 calendar days from the latest expected service date or up to 150 days after the service cessation date to file a claim.

Visa allows disputes for bankrupt providers up to 120 calendar days from the last date you expected to receive the merchandise or services, not to exceed 540 calendar days from the transaction processing date.

In other words, if your cruise doesn’t happen for another year and then the cruise line declares bankruptcy before you can set sail, you might be covered by your bank. But you would not have the same rights as you would under the FCBA. Your bank can go beyond its merchant agreement or the law to protect you if it wants. We have some cases where banks have allowed a dispute more than a year after a purchase — and sided with the customer.

It doesn’t always go that way. Here’s a case where one of our readers timed out and lost a dispute.

If you feel your credit card company isn’t following the law, you can file a complaint with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The best way to file a complaint is through its online form.

How do I dispute a charge on my credit card?

If you see a charge you want to dispute, the easiest way to file a chargeback is to visit your bank’s website. Most major banks will allow you to initiate a dispute online.

Your bank or credit card company will follow up with a request for documentation. So you’ll want to keep any supporting evidence, including invoices, receipts, and emails.

Your credit card issuer might hand off your request to Visa or MasterCard, depending on the type of dispute. The credit card network then makes the call on the validity of your chargeback after conferring with you, your issuer and the merchant.

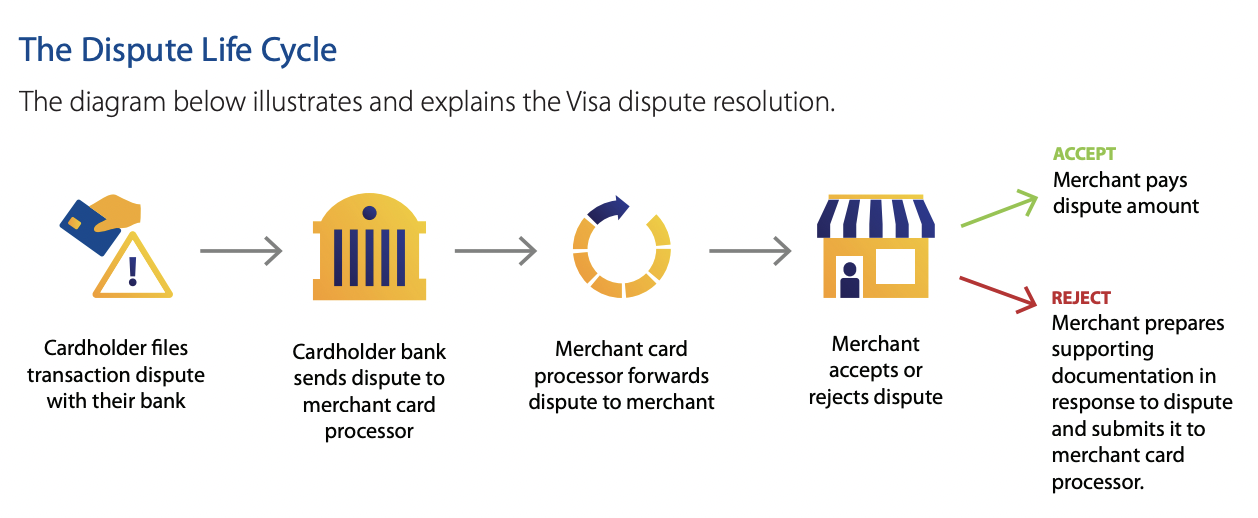

How does a credit card chargeback work?

When you contact your bank to dispute the charge, your credit card company will forward the dispute to the merchant. The business then either accepts or rejects the dispute.

You’ll usually receive a provisional credit on your card while your bank reviews the dispute.

Note: This is only a provisional credit. It does not mean you’ve won the chargeback. The business will get the money if the credit card company or bank decides in the merchant’s favor.

Credit card networks impose a chargeback fee on merchants when there’s a dispute. The merchant’s credit card processor sets these fees. Generally, businesses in high-risk industries will pay higher chargeback fees.

Most credit card disputes take less than 30 days. After the bank makes a decision, it will inform you in writing and either credit or debit your account. You may appeal the decision by submitting a second chargeback request and submitting additional documentation. If you disagree with the bank’s decision, ask to file a dispute resolution with the card network. The bank or card network usually has an arbitration process.

How to ensure your credit card dispute is successful

Your odds of successfully disputing a transaction are pretty decent. Businesses don’t even bother fighting most chargebacks, contesting only 43 percent of disputes filed against them. Just 12 percent of chargebacks go their way. But there are ways you can increase your chances of success.

The merchant must present “compelling” evidence of the charge

A business can’t just say “did too!” to get a charge to stick. Merchants must present “compelling” evidence of the charge, which includes enough documentation to reverse a meritless chargeback.

When you dispute a charge, the merchant will receive a notification from their payment processor. They’ll have an opportunity to accept or decline the chargeback, and if they decline, they will have to produce receipts, correspondence and other written evidence to support the charge.

So what is compelling evidence?

- Any written communication with you, especially emails verifying a link between you and the credit card purchase.

- A copy of the terms of use, cancellation policy or refund policy. (Read this carefully before filing your dispute.)

- Signed contracts or delivery confirmation receipts, including any signed orders or sales receipts.

- Screenshots that show you accepted the terms of the sale.

Conversely, if you have information that will prove your charge is not legit, this is the time to share it with your financial institution. I’ll have more on your documentation requirements in a second.

If the business can’t show the charge is on the up-and-up, it will probably lose the dispute.

Don’t file a “friendly” fraud chargeback

Friendly fraud is when you don’t recognize a charge or when someone in your household uses your card to make a valid purchase. Do your due diligence before filing a chargeback. Friendly fraud costs businesses billions of dollars annually and wastes everyone’s time. So don’t do that.

Avoid frequent chargebacks

Your odds of prevailing in your first chargeback are excellent. But serial chargeback filers are less successful. One recent survey of American consumers found that almost 15 percent of cardholders admit to filing five or more disputes in the past year. Nearly 6 percent have initiated more than 11 claims in the same period. These frequent chargebacks may lead to the termination of your credit card account.

Keep detailed documentation

All bills, invoices or emails that you receive in connection with the disputed transaction will help resolve your dispute. Get receipts, particularly for a big-ticket item. Keep all your documentation in an easily accessible format, like a Google Doc, that you can share with your bank or credit card company. Documentation will help win your dispute.

Find the credit memo

A credit memo is an email or letter from a business that promises you a refund. A text message from a representative promising you a refund is a de facto credit memo. That’s often enough for your bank or credit card company to side with you and close your dispute. If you can get something in writing that promises a refund, your chargeback will usually be a slam-dunk.

WARNING: Credit card disputes are the “nuclear” option

If you’re a regular reader of this site, you know that we refer to credit card chargebacks as the “nuclear” option. That’s because once a merchant wins a dispute, almost no amount of prodding from a consumer advocate will change the outcome. After losing a credit card dispute, your next course of action would be filing a lawsuit against the business.

As a consumer, you always want to make a good faith effort to resolve the problem. And I would underscore the “good” in good faith. Try everything before filing a dispute. Really.

Note: Even if you prevail in a credit card dispute, a company might still refer you to a collection agency or blacklist you. It could also sue you. Like I said, the chargeback is a nuclear option.

Strategies for a successful credit card dispute

I’ve seen a lot of successful — and unsuccessful — credit card disputes. Here’s what makes them work:

Getting everything in writing

I can’t overstate this. If you have receipts and messages showing this was an invalid charge, your credit card company’s dispute department will side with you. If you just have notes from a phone call, not so much.

A contract that says you’re right

If you can show the bank or credit card company a document that proves the company incorrectly charged you, then it’s an easy win. So always, always keep your contracts and end-user agreements, or take a screenshot of your terms of service.

Zero drama

One of the biggest mistakes that consumers make is amping up the drama. “You RUINED my vacation,” or “This appliance DESTROYED my kitchen.” That may play well with friends and family, but it lessens your credibility when dealing with a dispute department. Stick to the facts.

When to file a credit card dispute

Credit card disputes are the final lever, the nuclear option when all else has failed. Here’s when you should consider a dispute.

If it’s covered under the FCBA

If it’s a fraudulent charge or if you have documentation of a service paid for but not delivered, you have a green light to file a dispute. Remember first to give the merchant a chance to respond. You’ll need to let your bank know if you see an obviously fraudulent charge. It will close your account and reissue your credit card.

If you’ve worked your way up the chain and failed

I advise consumers with a problem to work their way up the chain — first to a manager, then a vice president, and finally the CEO. If you get to the end of the process and still don’t have a resolution, you can ask my team for help. And if we can’t? File a dispute.

If the merchant asks you to file a dispute

As strange as it sounds, we’ve had numerous cases where merchants have asked their customers to file a dispute. Why? Presumably, the dispute process is a faster way to refund, because the business will accept the dispute. This is one of the most inelegant ways of refunding a customer, and not at all what the system was designed to do. But it is what it is.

What if you lose your credit card dispute?

If your appeals fail and if arbitration is unsuccessful, consider filing a complaint with the CFPB. The bureau will share your complaint with the bank or credit card issuer, and it may reconsider its decision. If that doesn’t work, you might have the option of taking the merchant, bank or credit card company to small claims court to recover your loss.

If your credit card company can’t help you, cancel your card and find one that will side with you. Some banks are pushovers when it comes to disputes. They don’t deserve your business.

My experiences with credit card chargebacks

I’ve been on both sides of the chargeback equation — as a consumer and a merchant.

As a consumer, I’ve never lost a chargeback. I’ve disputed charges on merchandise that wasn’t delivered (a slam-dunk), on accounts that I canceled but kept getting charged (easy) and on a parrot I bought from a pet shop in the Florida Keys that died two days later (not so easy, but still successful). I’ve found that banks are generally on your side when it comes to disputes.

As a merchant, I’ve lost lots of disputes. I publish a weekly travel newsletter, and often, subscribers simply dispute the charges rather than cancel the subscription. It’s really annoying. No matter how much documentation I provide that they received the newsletter and that they signed up for it, the banks don’t care. They simply side with the consumer.

And over the last 24 months, the banks have become even more pro-consumer when it comes to chargebacks.

I’m telling you this not to encourage you to file a dispute — only to say that if you do, you’ll probably win — as long as you have the evidence mentioned in this article.

Sometimes, the best way to win a dispute is not to file one

Credit card disputes are an unfortunate but necessary part of the business ecosystem. Things go wrong from time to time, and we need a way to fix them.

A closer look at how the system works reveals that your odds of prevailing in a credit card dispute are excellent, whether you have a strong case or not.

Still, a thorough understanding of the process will lead you to one inevitable conclusion: Sometimes, the best way to dispute a credit card purchase is not to dispute it at all, at least formally. Use the proven strategies at your disposal to work this out with the merchant.

Bottom line: Don’t go nuclear with a credit card dispute unless you absolutely have to.